NOTE: This blog covers the theoretical foundations for the upcoming macro system. It is quite far from being actually implemented!

Macros and their design are easily what make Norg stand out the most in terms of extensibility. This post will focus around explaining - from start to finish - how Norg macros work under the hood and why they are considered so powerful.

This post assumes decent knowledge of what Neorg is and general understanding of the Norg file format. Feel free to have a read online if you’re not up to speed!

The Beginnings

Developing a macro system seems easy, but developing a good macro system? Oh boy. Having macros is not unique to Norg as a markup format, see Org and AsciiDoc as well as RST.

There’s one thing that is common to all of these formats, and it’s very likely you’ll agree with me here - macros are clunky. Want to extend a macro and make it your own? You’re bound to spend quite a while learning the syntax and behaviours of the macro engine to get it to do what you want.

This gives a bad first impression - do macros have to be this complicated? As it turns out, macros can not only be not ugly, they can also be elegant!

Quite recently typst has shown that adding functions to a markup language can greatly increase readability and flexibility:

#figure(

image("glacier.jpg", width: 70%),

caption: [

_Glaciers_ form an important part

of the earth's climate system.

],

)

While miles ahead of previous systems (like LaTeX), typst (as the name suggests) is a typesetting language, just like LaTeX is. Despite being

similar, the design that influences typesetting languages from markup languages is vastly different. Typesetting languages focus on predictable output

and design tending towards turing-complete programming languages, whereas regular markup formats are built for ease of use and ease of reading.

Something like Norg is, by design, much more human-centered.

To make a good macro system, one must tame both sides of the equation: the

syntax and the semantics. The syntax is the thing you physically type

(e.g. #figure(...) in the typst example above), on the other hand semantics

are the behaviours of the system (e.g. what #figure(...) actually means).

As syntax designers we can make function invocations look any way we might see

fit: #figure(...), $figure(...), (figure ...). We would consider these

different approaches different syntax, because they all look different. On

the other hand, they all mean the same thing (“invoke a function”) therefore

they have the same semantics. I hope that distinction is clear.

The rest of this post will describe, in full detail, the syntax and semantics of Norg macros. If you’re looking for a general overview, this is not the place to be. The amount of details will be excruciating here :)

The Foundations

Norg has a suite of syntax for dealing with macros called tags. Tags all relate to macros and custom data in some fashion.

Before we start discussing tags (along with their own subcategories), let’s define what a macro should be to begin with.

Simply put, a macro is an advanced substitution. A substitution is taking some content from one place and pasting it in place of something else. Let’s say we have a hypothetical syntax that looks like this:

$user:

vhyrro

Hello, $user!

At the top, we define a macro called “user”. This macro evaluates to “vhyrro”. Therefore, when the second $user directive is read a

substitution is performed. The $user directive is substituted for vhyrro, yielding:

Hello, vhyrro!

Thinking of something this complex as just these simple substitutions will prove to be critical later on!

The reason why we call these things macros and not substitutions is that macros can take arguments. We could extend our hypothetical language to accommodate for this in the following way:

$greet(user):

Hello, $user!

Here is a greeting:

$greet(vhyrro)

It may seem weird why I’m being so explicit about all of these foundations, but bear with me for a moment. Notice anything weird about the parameter

syntax? No? When we think of parameters, we usually think of them as distinct objects (distinct syntax). But do they have to be so? Let’s change the

$greet(user) to $greet($user):

$greet($user):

Hello, $user!

Here is a greeting:

$greet(vhyrro)

Notice how, with a single extra character, we have made the situation clearer: parameters can also be represented as macros themselves! If you’ve done programming with dynamic languages like lisps before, you’re probably not impressed, but to everyone else - this is important.

Let’s imagine we now want to expand the macro invocation in the document, let’s tackle the problem step by step:

- First, we evaluate the

$greet(vhyrro)macro. We know that evaluation is the same as substitution, but how do we handle parameters? Like other macros, of course! We expand the parameter with contentsvhyrrointo its own macro, thus giving:$user: vhyrro $greet: Hello, $user! Here is a greeting: $greet - Evaluation happens bottom-up, thus we now evaluate the

$greetmacro - this is a simple substitution:$user: vhyrro Here is a greeting: Hello, $user! - Now all that’s left is substituting

$userfor the correct value and we get the final result!Here is a greeting: Hello, vhyrro!

To recap, macros are simple substitutions at their core, and macros with parameters can simply be broken down into more fundamental macros.

When to Execute Macros

Macros should never run on their own within any document as that would pose a severe security threat.

We distinguish two main ways of “activating” the macro - baking and previewing.

-

When we “bake” a macro we irreversibly collapse the macro into its final form. This is a one-way operation - all invocations of the macro are substituted for the final value.

Not all macros are bakeable, but that’s a discussion for later on.

-

When we preview a macro we simply peek at the result but do not replace the actual macro invocation. The output of the macro is displayed e.g. in another window or as virtual text within the document.

This action is non-destructive - it simply allows the user to preview what their macro would do.

No matter what invoking a macro should always be a manual operation by the user - either through a keybind or through a command.

The Macro Tag in Norg

Now that we conceptually get what it is we need to implement, let’s actually do so in the context of Norg, not in the context of a hypothetical syntax. Tags are a category of the Norg syntax that include ranged tags, carryover tags and infirm tags. If that feels like a lot, fear not, let’s focus just on one category for now: ranged tags. Whenever you hear “tag” in the context of Norg, immediately think “this has something to do with macros”.

Ranged tags are characterized by their start directive, some content and an end directive.

One such type of ranged tag is the macro tag which defines a macro:

=user

vhyrro

=end

Easy! We now have a macro called user with the contents vhyrro. We can use the &..& syntax to expand the macro:

=user

vhyrro

=end

Hello, &user&!

If we were to evaluate this whole document (just like we did in the previous section), we would get:

Hello, vhyrro!

What about parameters? Simple! Place them after your macro name, space separated:

=greet user

Hello, &user&!

=end

Problems Already

It’s only 100 lines of Markdown into the post, and we already have issues?

You see, the &...& syntax can only invoke macros without parameters. Since

greet takes in a user parameter we can’t use &greet& to invoke the macro.

See the footnote to understand why in greater detail, if you’re interested1.

To invoke a macro with parameters we may opt to use the infirm tag. “Infirm” means small, less significant, which is a fitting name in the context of the other tags.

Infirm tags start with a full stop (.) and look like so:

=greet user

Hello, &user&!

=end

Below is a greeting:

.greet vhyrro

And indeed upon expanding the document we’d get Hello, vhyrro!.

Quick note: we can also rewrite the first Norg example using infirm tags too:

=user

vhyrro

=end

Hello,

.user

Using the inline syntax (&user&) just proved to be simpler in that context. Therefore

for macros without parameters ¯o-name& and .macro-name are almost equivalent2.

Going Further

Alright, so we have some syntax for defining a basic macro with parameters.

We can invoke this macro using the infirm tag (.this) or using the inline macro

expansion (&this&) if the macro takes no arguments.

But macros like this don’t really do much on their own. Sure, they can simplify some copy-paste tasks or they can shorten some repetitive tasks - but to be a fully fledged macro system we need so much more! We need scripting, we need manipulation of the document. We’re getting there.

To reach the next level of macro expressiveness we need some way to interact with the underlying Norg document. What you might be surprised to hear is that this merely needs some new syntax, we don’t need to change any behaviours of the macros themselves. Let’s see this through an example - carryover tags. If you’re cheeky you may have deduced through their name that they carry over to something.

Contrary to infirm tags (.macro-name), carryover tags (#macro-name) still

invoke a macro, but they invoke a macro on an object. To illustrate, how

about we create a remove macro? This macro, when applied on an object, will

completely remove it from the document:

=remove next

=end

We create a macro called remove and we take a parameter called next… and that’s it! Think about it,

we want the content of the macro to be empty. Since macro invocations are substitutions, our object

will be substituted for emptiness, therefore removing it from the document.

next is just a parameter like any other, but we call it next as a convention. Before we explain that, let’s

try to invoke our macro with the infirm tag:

=remove next

=end

.remove remove_me

If we were to evaluate this macro we would get nothing back, our macro is working!

When we use the carryover tag, the object below the carryover tag itself is

automatically supplied as the last parameter to the macro, that’s why we call

the parameter next - we’re expecting that parameter to be the next object.

Enough talking, here’s the example:

=remove next

=end

#remove

Here is a paragraph that I would like to remove.

Carryover tags are placed above the item you would like to operate on, and the next item is consumed and fed as a parameter into the macro! If you’ve read the foundations section carefully you can guess how this all works under the hood. To evaluate the macro with parameters an application like Neorg would break it down into smaller, simpler macros:

=next

Here is a paragraph that I would like to remove.

=end

=remove

=end

.remove

And then evaluate the .remove macro, which would yield emptiness and leave us with:

=next

Here is a paragraph that I would like to remove.

=end

But since the next macro is not invoked/used anywhere it is pruned, thus leaving us with an empty document!

The example I provided you with might seem a tad stupid or useless, but it

actually exists in the official Norg standard library! It’s called comment

and it can comment out (in other words remove) any portion of text that you

give it.

Arbitrary Parameter Counts

If we’re unsure how many parameters our macro will take in we can use special suffixes to capture

an arbitrary amount. Here’s what the implementation of comment actually looks like:

=comment params+

=end

#comment

This is my text!

This also has the benefit of capturing any extra parameters:

#comment Some parameters that will also be dropped

This is my text!

These are officially called quantifiers. There are three quantifiers:

?- means “zero or one occurrence”*- means “zero or more occurrences”+- means “one or more occurrence”

This means that the comment macro expects at least one variable to be provided (e.g. some text or some content),

which makes sense. What use is a comment without the comment body itself?

There is one rule related to quantifiers: there can only be one quantifier in a parameter list.

Imagine a situation like this:

=mymacro some-parameters* other-parameters+

=end

Upon invoking the macro with e.g. .mymacro one two three four which parameters should belong to some-parameters and which

to other-parameters? To prevent confusion, only one quantifier is allowed at a time in such a list.

More Ranged Tags

We’ve learned how to invoke macros in a standalone fashion (the infirm tag) as well as macros invoked on an object (carryover tags). What about macros invoked on a range of objects? This is the last piece of the puzzle in order to create a functionally complete macro system.

You’ve already seen the macro ranged tag which was used to create a macro. There are two others - the standard ranged tag and the verbatim ranged tag. These invoke a macro with arbitrary content.

Standard Ranged Tag

The standard ranged tag treats the content as Norg markup. Let’s use the previous example of the comment

tag to illustrate.

First, we define the macro:

=comment params+

=end

Then, we invoke the macro by using a standard ranged tag:

|comment

Here is a long comment!

I can put anything I want in here, /including/ markup!

|end

Once the macro is evaluated, it yet again gets converted down to nothing.

Verbatim Ranged Tag

The verbatim ranged tag behaves generally the same as the standard ranged tag but its content is not valid Norg markup. This distinction is surprisingly important, see the footnote for more information3.

An example of such a macro invocation would be the @code tag:

@code lua

print("Hello *world*!")

@end

You definitely do not want the *world* to be interpreted as bold in this case.

It’s also entirely possible to invoke the comment macro using the verbatim ranged tag:

@comment

It's just that in this case *there is no bold*!

Not like it makes much of a difference with this macro...

@end

Quick Recap

Before we move on to scripting, let’s recap:

- Macros are defined using the

=macro-name ... =endsyntax - Macros can be invoked in different ways depending on the context in which the user wants to use them:

- In a standalone fashion, in which case you use the

.macro-nameinfirm tag - On an object, in which case you use the

#macro-namecarryover tag - On a range of Norg markup in which case you use the

|macro-namestandard ranged tag - On a range of non-Norg text, in which case you use the

@macro-nameverbatim ranged tag

- In a standalone fashion, in which case you use the

- Expanding the macro is as easy as separating its parameters into other macros, then evaluating all macros in a bottom-up fashion.

If you understand all of these fundamentals, then you’re ready for the next stage: scripting.

Scripting

Regular substitutions are not enough to build complex macros. In order to create effective scripts, one needs a scripting language.

If you’ve had a hard time grasping everything before this section, I have no words of comfort for you, it’s not going to get any easier from here!

How, you may ask, do we even start embedding a scripting language into a simple substitution-based mechanism? To fully achieve this we need two more features - a scripting language of our choice and types.

Choice of Scripting Language

After a long search for the perfect scripting language, Norg finally landed on one specific language: Janet.

Janet is a lisp, but do not let this deter you in the slightest. Below is a list of reasons we chose Janet, directly copy+pasted from our design decisions document in the norg-specs repository.

Lisps are Good with Structured Data

Love them or hate them, lisps are physically built for working with objects that have structure to them. In Norg, structures are all over the place, most notably in the form of document nodes. Any part of the Norg document can be accessed and every item (a list, a heading, a paragraph) can be manipulated and viewed in the form of a node. Many nodes then build up a tree which constitutes the entire document.

Manipulating data related to these nodes is frictionless in a lisp as in a lisp everything is data. Weaving complex operations together takes no effort and is much simpler to reason about in comparison to e.g. a pure functional programming language like Haskell or a fully imperative language like Lua.

Janet is Easy to Reason About

Janet reads just like an imperative language - a sequence of steps that are performed one by one. Brackets mostly signify scope. This similarity of thought processes just like in imperative languages makes any common programmer feel right at home.

Janet is Lightweight

Janet is an incredibly lightweight language. Its interpreter was built to be fast, portable and also small. Tight integrations with C means there’s little code duplication around. The syntax of the language is also small and predictable, similarly to how Lua has a small but effective syntax set.

Janet is Portable

Because of its simplicity and portability Janet sees many integrations with other libraries. Parsing things

like JSON or TOML is wonderfully unsophisticated. Janet even sees bindings for tree-sitter and more.

Janet Has a Built-in PEG Parser

This is easily the biggest selling point of using Janet as a primary scripting language for Norg. There are many

situations where you might want to parse a snippet using Janet. These usually involve areas where the Norg

tree-sitter parser cannot reach, i.e. content of verbatim ranged tags or custom parsing of macro parameters.

PEG is a combinatoric parsing library. In layman’s terms, it allows you to combine simple parsing functions together to form a more complicated parser like Lego bricks.

A prime example of a use case within Norg is the @table macro. @table allows the user to write a table using

Markdown-like syntax which then gets translated to the more verbose Norg table syntax. Parsing the Markdown-like

table is not the job of the Norg parser, rather, it is up to the macro itself to properly parse the contents of the

verbatim ranged tag. For this reason a scripting language with good parsing support is critical and an inbuilt PEG

implementation is perfect for what we need.

To summarize, finding a scripting language that:

- Works very well with structured data.

- Is approachable by almost any common programmer.

- Is lightweight, simple and extensible.

- Has parsing capabilities built in.

Proves to be mightily problematic without resorting to esoteric languages (hence breaking the second bullet point).

In our hours of searching, Janet was the only language that not only fulfilled those criteria, but also provided more

with a working package manager and a well-featured, community-maintained extension library (spork). We believe this

is as close to a perfect scripting language for a markup format as is possible!

Type Prefixes

Up until this point Norg macros have made no distinction about types of data.

The user is entirely free to invoke a macro in any way they please through any tag type. There are cases where you may want to limit this freedom, e.g. you want your macro to be only invokable from the context of a carryover tag, or only from the context of a verbatim ranged tag, whatever.

To enforce this, you may prefix your variable name with a type prefix. Below are the available prefixes:

#- carryover tags only@- verbatim ranged tags only|- standard ranged tags only&- macro only

These type prefixes are most commonly used for the next parameter:

=mymacro #next

The content of the next variable is: &next&

=end

Now, with the # type prefix, mymacro can only be used from a carryover tag:

#mymacro

some text <- WORKS: Generates "The content of the next variable is: some text"

.mymacro text <- FAILS: This will issue a type error

Macro Capture Prefix

What’s with that & prefix? As the name suggests, the & syntax is used for capturing macro names.

This is easily understood with a visual example:

=my-macro

some content

=end

=other-macro &variable-list+

=end

.other-macro my-macro

^^ SUCCEEDS: `my-macro` is the name of a valid macro

.other-macro my-macro some-nonexistent-macro-name

^^ FAILS: `some-nonexistent-macro-name` doesn't exist

You will almost never use this type prefix in your own macros, but they’re important to ensure the rigidity of some internal macros that Norg bundles in its standard library.

Simply put, the & prefix expects a name of a valid, existing macro and will error otherwise.

Special Behaviour of &

The & prefix has one special bit of behaviour - it’s greedy. When put

together with the * quantifier, & will try to consume as much as possible -

this means that if the user supplies no parameters to the variable it will

capture all existing variables in the current scope.

Say we create a parameter &variables*. If the user supplies some valid macro names in place

of variables then nothing special happens. If the user supplies no macro names at all

then variables will be populated with all macro names in the current scope.

Seems random? Now it’s time to explain how all of these seemingly random facts fit together to make Janet work with Norg.

Bootstrapping Janet

We’re ready to start bootstrapping Janet into the macro system. To do so, we need to lay out a few foundations that will allow this bootstrapping process to be smooth and simple.

Neorg-like Applications

Before we move on to the way Janet works with macros, let’s discuss what a “Neorg-like” application is.

Neorg is not designed to be a walled garden and therefore we define, using a specification, what it takes to reimplement Neorg elsewhere for your favourite text editor.

We call these reimplementations of Neorg “Neorg-like” applications.

For a Neorg-like application to fully support macros, it must have the following:

- Correctly implemented logic for macro expansion.

- Correctly implemented type checking (for type prefixes) and quantifier matching.

- A bundled Janet runtime.

- Implemented support for

.invoke-janet. - Implemented support for

(neorg/execute).

It’s easy to understand the first three requirements, but what about the last two?

.invoke-janet

It’s impossible to create a perfectly self-describing system (see Gödel’s incompleteness theorems), so we need to cut corners somewhere. This is one of them.

invoke-janet is a macro that must be implemented within the Neorg-like application itself, as it’s impossible

for Norg as a format to execute code on its own without a runtime. The Janet interpreter exists on the application side,

so it must be run from the application side.

This macro can only be invoked as an infirm tag (.invoke-janet). It takes an arbitrary amount of parameters

which are the Janet code that the Neorg-like application should execute.

If the Janet code returns a string, the output of the macro is the contents of that string, otherwise we issue a type error.

(neorg/execute)

As the parentheses suggest, this is a Janet function. Norg bundles a standard library that any Neorg-like

application is expected to ship. This standard library consists both of builtin macros (like comment or code)

as well as builtin Janet functions (neorg/func-name).

The Janet standard library is only partially implemented. This is by design. There are many aspects of Norg’s backend that differ from application to application.

For example, different applications may use completely different parsers for reading Norg files.

Neorg uses tree-sitter, but others may opt to use anything else under the sun.

Norg’s stdlib has its own parser-agnostic representation of a node, but you will eventually have to

convert between your own internal representation and the parser-agnostic representation.

Therefore functions like (neorg/from-object) are left to the Neorg-like application to implement by themselves.

This gives everything a consistent API but allows complete freedom in what tools the backend uses as long as it

implements the “glue” functions.

(neorg/execute) also belongs to this “unimplemented” list of functions. This function’s sole purpose

is to execute some code. Usually this code is other Janet code but, here’s the twist, it doesn’t have to be

Janet code.

This opens up the possibility for other applications to bootstrap their own programming languages for use in Norg macros - lua, python, haskell, anything. We frankly think this is incredible, and we hope you do too!

To run a custom macro in your own programming language, you would do something similar to the following:

.invoke-janet (neorg/execute "python" "print('Hello!')")

This would invoke the (neorg/execute) function that you yourself had to

implement, allowing you to forward the execution to a python runtime of your

choice! Notice that you must pass through the Janet runtime in order to execute

other programming languages’ code, this is again by design - Janet should be

the defacto language that everyone uses by default. For maximum portability it’s still

recommended to write your macros in Janet.

Reimplementing the Macro Standard Library

You now have all of the fundamental knowledge required to reimplement the Norg standard macro library! You know that the Janet part of the stdlib is only partially implemented, which gives us a lot of room for abstractions.

This section will reimplement the first few macros of the existing standard library one-for-one to hopefully give you a full understanding of what’s happening behind the scenes.

Before you move on, a general idea of how Janet syntax works is expected of you. You don’t need to be an absolute wizard, but a general grasp is necessary going forward.

NOTE: Do you remember how I said in the beginning of this post that the macro system is generally elegant? It’s definitely the opposite when you’re trying to reimplement the stdlib from scratch. There will be some elements that have to be ugly!

Let’s create a stdlib.norg file and put our new implementation in there.

The Basics

Let’s start off by adding a nice comment to the top of the stdlib, and defining

the comment macro right afterwards.

#comment

This is the start of the Norg Standard Macro Library (NSML).

=comment params+

=end

Bootstrapping Janet

Here’s the hardest part, we need to somehow synergize both invoke-janet and (neorg/execute)

to do what we want (which is executing Janet). The easiest way to do this is to define a #eval tag.

This #eval tag will attach itself to a code block containing Janet code and run the code within.

This will nicely prevent us from having to write one-liners everywhere using .invoke-janet.

Here’s what we want to achieve:

=my-cool-macro

#eval

@code janet

(print "Hello!")

@end

=end

&my-cool-macro& <- running this macro will print "Hello!"

… and here’s how we’d achieve it:

=eval &captures* #code

.invoke-janet (neorg/execute '[&captures&] (or (neorg/ast/ranged-verbatim-tag? ```&code&``` "code") (neorg/ast/ranged-verbatim-tag/content ```&code&```) (error "Expected code block to follow \`#eval\` block!")))

=end

There’s a bit to dissect here:

-

Firstly, we’re capturing all available macros in the current scope through the greedy

&type prefix (remember this bit about the macro prefix?). -

Secondly, we’re capturing the next object using the

#type prefix -

The content of our

#evalmacro consists of the.invoke-janetcall which runs(neorg/execute). -

We feed both the captured macros and the contents of the ranged tag into the execute call, formatting it in such a way that it’s not misrepresented as Janet code (e.g. ```code``` prevents the contents of the code block we provided from being treated as instructions)4.

The Janet code may look really wonky and that’s since we need to stretch it all out on a single line. I recommend getting used to Janet a little bit if you’re unsure what the quoting operator (

') does or if the(or ...)statement looks foreign!The content of the

orstatement ensures that the verbatim ranged tag is indeed a code block (@code) and if so forwards the contents of the code block to the(neorg/execute)function, otherwise it prints an error.

That’s all we really need! Now we can write other, more concise macros.

Next up, let’s create another convenience wrapper that will allow us to write macros faster.

=macro name params* #next

#eval

@code janet

(def wrong-next-object "`macro` requires that the next object be a `@code` tag!")

(assert (neorg/ast/ranged-verbatim-tag? next) wrong-next-object)

(let [next-tag (neorg/ast/ranged-verbatim-tag next)]

(assert (= (get next-tag :name) "code") wrong-next-object))

(string "=" name " " ;params "\n#eval\n" (neorg/ast/node-text next :join) "\n=end")

@end

=end

This macro uses our #eval wrapper for ease of writing. Let’s break the Janet code down:

- First, we define an error message for easy reuse called

wrong-next-object. - Next, we check if the

nextobject is a verbatim ranged tag. - We use the

(neorg/ast/ranged-verbatim-tag)function which parses thenextobject into a table which we can access data from. We do this to see if the name of the ranged verbatim tag iscode(which is what we expect), otherwise we issue an error. - We return a string containing the resulting Norg output that we care about.

To fully illustrate how this macro works, here’s an example of it in use:

#macro mymacro some-parameter

@code janet

(print some-parameter)

@end

Upon expansion:

=mymacro some-parameter

#eval

@code janet

(print some-parameter)

@end

=end

Code Blocks

Now let’s move on to implementing the @code tag. @code can take in a single

parameter optionally signifying the language.

Creating the template for this macro should be incredibly simple:

=code language? @content

=end

But wait, what should the macro evaluate to? Code blocks have no physical Norg markup that backs them, so how do we represent such a macro?

This is where abstract objects come to the rescue.

Abstract Objects

It’s not always the case that a macro can evaluate to something physical, although that is definitely the most common case.

Some macros like @code have no way of being represented, so what does their respective

macro evaluate to?

You may recall earlier in the blog that Janet macros can return a string, in

which case the regular old substitution ritual is performed. But, instead of

just returning a (string) one can also return a (neorg/abstract-object)

class.

Abstract Objects (AOs) are an opaque data type within Norg. They serve as a way to represent some intermediate information about an object without having concrete Norg markup backing it.

Abstract Objects have a few builtin properties - some must be provided, whereas others are left as optional:

- A single/list of translation schemas (required)

- Custom data that the AO would like to keep for future reference (optional)

The translation schema is the most important part of an abstract object. The translation schema is basically

a description of what the object represents. In the case of @code the macro could return a schema

that says something along the lines of “I’m a code block”. How is this useful in the slightest?

Imagine a Neorg-like application wants to export the current Norg document to Markdown.

Upon encountering an @code invocation, what is it supposed to do?

The Neorg-like application can run the macro, see that it returns an abstract object, and read the schema data. Norg defines a list of known schemas that every Neorg-like application should support for e.g. export purposes. The application would see that the abstract object has a schema of type “code block” and would then invoke the correct logic for exporting to a markdown code block.

Custom schemas are also permitted and any application that does not recognize the schema can issue an error to the user or ignore that specific macro.

Bakeable vs Unbakeable Macros

This leads us down an interesting path of reasoning - macro substitution mustn’t always succeed.

If the macro evaluates to regular Norg markup or a regular string via Janet, the substitution is performed.

If the macro returns an abstract object then the macro cannot be substituted, as there is nothing you can substitute it with.

For this very reason we say that not every macro is “bakeable”. If a macro can be baked, that means it can be irreversibly collapsed by substituting the output of the macro in place of the invocation.

If a user tries to evaluate an unbakeable macro then an error should be issued.

This is logical, it would make no sense to irreversibly bake an @code block, how would that even work?

Implementing @code

With all of that information in mind, here’s the full implementation of @code:

#macro code language? @content

@code janet

(neorg/abstract-object :schema (neorg/schema/code-block content :language language))

@end

So simple!

Winding Down

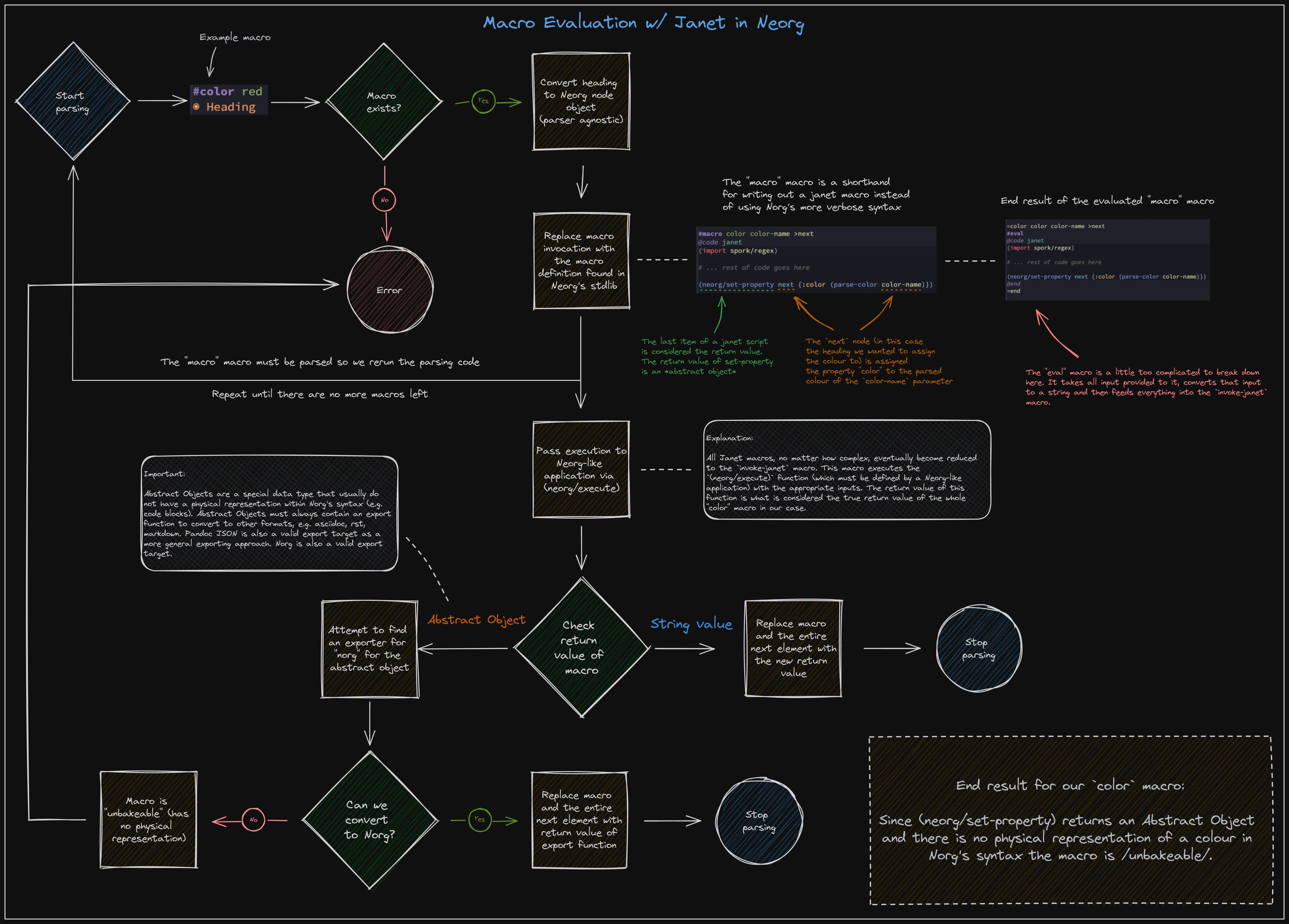

That was your all-in-one introduction to Norg macros. I recommend you re-read the visualization for Norg macro execution that I made at the very top of this blog post and see if you now understand it!

In this blog we explained from the bottom up how the entire macro system should work, accounting for every edge case we could humanly consider.

What I find particularly elegant about this whole implementation is that there’s no one thing you can point at and go “this is complicated”. Every component that makes up the macro system is simple. When you start composing all of these aspects together you quickly find that you can do basically EVERYTHING with this macro system.

The Janet Sandbox

There’s one last thing I need you to know. Everything Janet does is done using the Janet sandbox.

Norg by default completely disallows filesystem access, FFI, spawning subprocesses, reading/writing environment variables as well as accepting inbound network connections.

Conclusion

Before I conclude this blog, it’s important to address the whole “elegance” ordeal. You may feel a bit cheated as some of the syntax you’ve seen has been far from elegant.

Remember, I showed you the ins and outs of the entire system, including how to reimplement the standard library from the ground up. Bootstrapping is almost always verbose…

Think about the macro system from the user’s perspective. In their daily usage they’ll never

delve into the depths of bootstrapping Janet. That’s a sign of good abstraction - the user doesn’t

have to care at all about the fact that &this* captures all macros in the current scope, nor do they

have to know that macro parameters are in of themselves macros.

In most cases they’ll be making basic macros to simplify their workflows or using macros that

others have made for them. Want to transform an object? Slap a #macro on top. Want to embed

an image somewhere? No problem, .image /my/image.png. Despite the chaotic interactions that happen

underneath, the surface is completely stationary and stable, and that’s what I think is beautiful.

Thank you for taking the time to read this. I hope you learned something useful from this; syntax design is incredibly nuanced, so it’s always nice to know when someone else appreciates it too! :)

Footnotes

-

The

&...&syntax exists as a form of expanding simple macros only. Contrary to the infirm tag, which preserves the output of the macro, the&...&syntax converts all newlines to spaces before placing it in the syntax tree.Not only this, the AST output is hashed and compared before and after the newline conversion to make sure no data was actually altered. One may say: why go through all these troubles? I say, what happens when you try to expand a macro that returns e.g. a code block in the middle of a paragraph? There’s no valid way of handling that and, believe us, we tried.

This is precisely why the inline expansion syntax is so limited. Macros without parameters are much more likely to return simple content that we can flatten and which won’t break the flow of the paragraph. ↩

-

Both invocations are not exactly equivalent as the infirm tag fully preserves whitespace, whereas the inline invocation converts all newlines to spaces before expansion. See the first footnote for all the details. ↩

-

The best way to illustrate the importance of this distinction are code blocks. As you know,

@thisis valid Norg markup. Imagine trying to create a java code block while allowing Norg markup inside:|code @MyDecorator class MyClass {} |endOops, you’ve just started a

@MyDecoratorblock which you now need to close with@end.On the other hand, there are cases where you need nested markup. There are special macros like

|group(for grouping content) or|example(for displaying an example of Norg markup). If those were only accesible from@tags, then you get the same problem: you can’t create nested tags inside:@example @code @end <- OOPS, this ends the example block @endThe duality of both of these tag types is therefore critical for the functioning of the macro system. ↩

-

There is a “security flaw” with this code. If a code block contains more than three backticks then you can escape the Janet string and theoretically execute arbitrary Janet code.

The reason this is not a flaw is because macros don’t run on their own - they need to be manually invoked by the user. This means that by running the macro the user already expects code to be executed.

This would only be a security flaw if the sandbox code were implemented in the

(neorg/execute)function. This string escape would therefore bypass the sandbox by running code outside of theexecutefunction. It’s critical, therefore, that the sandboxing is implemented in the.invoke-janetmacro on the application side. ↩